The Creative Process

Scandinavian song researchers make a fundamental distinction between two main categories: folk songs and literary songs. To put it simply, this distinction is based on whether the creator is known. When it comes to literary songs, Swedes most often think of such songwriters as Carl Michael Bellman, Barbro Hörberg or Cornelis Vreeswijk. It can, of course, be anyone at all — if there is an identifiable creator. The creators of folk songs have not been identified. These songs have been sung as part of folk culture and transmitted from person to person — often for generations. Most agree that this distinction can at times appear to be contrived since folk songs too must once have been created by a person. Prison songs seem to be somewhere in between. Most of the older prison songs do not have known creators — but not all. In many cases, a writer of the text is indicated, often the perpetrator of the crime that the song portrays. This is a hallmark of the song’s authenticity, an assurance that the song is a correct testimony. Sometimes a singer who is well-known in the prison environment is said to have created the song: this too appears to raise the status of songs. Karin Strand presents a similar discussion of “authenticity markers” in her analysis of songs of the blind:

“On other occasions it was palpably not a matter of original creation — for example, in such cases where the same song with only small variations is found with different titles in songs published by different persons. The text is however individualised by changes in the names of persons and places and concrete circumstances and even the melody named can vary. This phenomenon is best termed as the written creation of variants based on a certain song or type of song, for pragmatic or commercial reasons. […] Since the true author’s identity was seldom disclosed, the self-same song could be attributed to different persons.” (Strand 2016:36)

When it comes to prison songs, we find several examples of how the names of persons and places are changed to create a sense of both timeliness and authenticity. One example is “Härlandavisan” [The Härlanda Song] which is changed to “Långholmsvisan” [The Långholmen Song] by changing the name of the prison. Literary songs have, as stated, a known creator, and another characteristic is that they are most often manifested in writing. This means that there is a written original. This is not normally the case with prison songs. Since they are most often found in a socially-based tradition without originals, different versions of songs are constantly created. This is, on the other hand, typical of folk songs in general.

We have noted that prison songs are transmitted from inmate to inmate orally or in writing. They were spread in prisons when inmates had a chance to mix and spread from prison to prison on account of many inmates serving sentences in many different institutions. Each individual put a personal stamp on a song and even though they were written down in songbooks, text variants arose — this is clear from Svenskt visarkiv’s material. This is in other words a song category between folk song and literary song. We can assume that the songs were created or used by individuals with a need to express themselves via songs or poetry. For many people in vulnerable groups, the songs provided an opportunity to express themselves, communicate messages and share both experiences and feelings. In addition to songs being a suitable medium for expressing both feelings and opinions, they were often the only way that less well-off groups on the margins of society could publicly express themselves.

The Solitary Confinement Cell as a Writer’s Cottage

A few studies show that isolated collective communities can stimulate creative processes. In the anthology Samlade visor. Perspektiv på handskrivna visböcker [Collected songs. Perspectives on handwritten songbooks], ten Swedish ethnomusicologists, historians and text researchers present various perspectives on handwritten songbooks (Ternhag 2008). These songbooks were broadly used by Sweden’s general public from the second half of the 1800s. Around the turn of the century, 1900, they were most frequently in use — almost every young person had one. The typical songbook is a notebook with black oilcloth covers in which well-known songs were written down. They were used by both women and men, particularly young people. Certain patterns are discernible: women wrote in their teens and before marriage.

Men wrote first and foremost in periods when they found themselves in collective homosocial communities. Examples of this are handwritten songbooks once owned by recruits, seamen, railway navvies and firemen. In Svenskt visarkiv’s collections, there are around a thousand handwritten songbooks — originals or copies — but only a handful consist of prison songs. My intention here is not, however, to discuss the songbooks as such, but the time in prison as a premise for the creation of music.

Lennart “Konvaljen” Johansson tells of how he was prepared to go to almost any lengths to avoid the isolation cell. One ruse was to harm yourself so that you ended up in the prison hospital. Here he shows his forearm, with long scars from when he cut himself to get a transfer. Photographer: Dan Lundberg.

It has been pointed out that living in solitary confinement could have a positive effect on a prisoner’s creative activities. This could — for those not broken down by tedium and loneliness — give time for afterthought and writing, for example, songs or poetry. But even after 1945, when the isolation of inmates decreased, there was plenty of time to read and write. The increased possibility of mixing with others also meant that many inmates learned songs from one another.

The Prison Revues

New Year revues were staged at the Långholmen prison in Stockholm as early as the end of the 1940s. The prison revues displayed a similar spirit to popular revues in general. They gave inmates a chance to comment, criticise and mock their superiors — warders, police, psychologists, etc.

But one day when I am free

Then I will try to be

Honest and conscientious so perhaps I

Can be a warder in clink one day.

A uniform like a warder has

With brass buttons here and there.

And when he walks there on his watch,

A key as a symbol of his power.

(Tjuvarnas dag är slut [The Day of the Thieves is Done]),

Långholmen Prison,1965)

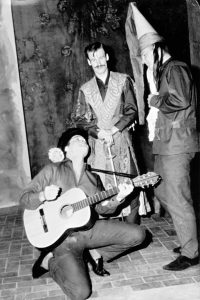

Jailbird Singers in a revue from Långholmen in 1964. The director was a fellow prisoner who was a famous theater worker. The revue was based on Ruben Nilsson’s show Trubaduren [The Troubadour]. The scene depicts a jealousy drama in a medieval setting between a count, a troubadour and a countess. Tony Granqvist (the troubadour), Åke Johnsson (the countess) and Tohre Eliasson (the count). The photo is privately owned by Tohre Eliasson.

Kommentarer