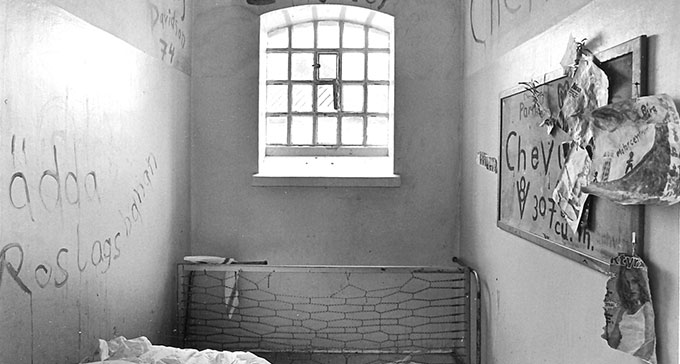

Cell in Centralfängelset "Västra 2", Långholmen. Documentation from Nordiska museet, 1975. Photographer: Nils Blix.

What are Prison Songs?

We have called the material upon which this study is based “prison songs” [Swedish: kåklåtar or kåkvisor]. But what are, in fact, prison songs? As often, when it comes to folk and popular music, the terminology can be diffuse and vague.

Many different names occur in the interviews. Two of the studies in this field attempt to define the genre. In the essay Om innehållet i kåkvisor [On the Contents of Clink Songs], Rita Berggren and Sylvia Hardwick write that they study:

“…songs written by prisoners and passed down within the walls. We feel unable to impose limits based on contents — that they must, for example, be about prison. In our opinion, clink songs can in general be about anything at all — though they will naturally be confined to certain spheres of interest. The prisoner writes about what is relevant to him in his situation.”

The music researcher Gunnar Ternhag defines prison songs as “… Songs written and sung in prisons, about prison or crime environments”. In other words, Berggren and Hardwick impose no limitations on the contents of the songs but ask that they should be written by prisoners and passed down in prisons. Ternhag, on the other hand, demands in addition that the contents of the songs should concern prison and/or crime environments. Another feasible criterion of the genre might be practice: that the songs are sung by prisoners, which might well be more decisive than that they were written by prisoners. The fact is that we are often, as with many song genres in which songs are passed down, unable to say who wrote either words or music. We can assume that they were written in a prison environment by prisoners, but the people who wrote them are for the most part unknown. When it comes to genres associated with particular groupings it is common to critically reflect on affiliation by discussing the senders, receivers and themes of the songs. Who sings, for whom, and about what? The text researcher Bengt R. Jonsson reasons in a similar way regarding emigrant songs.

“The question may in part be formulated thus: are emigrant songs about, by or for emigrants? This same question arises about, for example, songs of sailors and soldiers. And as with these other categories we find different answers from case to case.”

Prison songs resemble other kinds of trade songs or work songs (if crime is to be regarded as a “trade”?!). One of the more well-publicised sub-groups within the work songs category is the songs of the railway navvies. The Swedish musicologist Margareta Jersild and text researcher Bengt R. Jonsson suggest that the songs of railway navvies comprise both songs directly connected to work activities when building railways — used to synchronise collective efforts — and songs directly concerning railway navvies and their work. The songs used to synchronise collective efforts have of course no counterparts in the prison songs genre, whilst the other category certainly has. Jonsson and Jersild suggest, in other words, that the railway navvy songs in the latter category are songs about “railway navvies and their work in general”. Such a definition does not demand that these songs must be sung by railway navvies or written by them.

If we apply the same argumentation to prison songs, this would imply that a prison song might be written and performed by someone who had never set foot in a prison. Cornelis Vreeswijk’s song “Mördar-Anders” [Anders the Murderer], written for the group Jailbird Singers’ LP Tjyvballader och barnatro [Thief Ballads and Childhood Faith] (1964) is a thorny case. The group consisted of three prisoners from Stockholm’s Långholmen prison. After the group’s LP had been released, Cornelis sang the song himself when he, together with Ann-Louise Hansson and Fred Åkerström, released the LP Visor och oförskämdheter [Songs and Insolences] a year later. Since Cornelis (then, at least) had not served time, it is feasible to say that Mördar-Anders was not a prison song when Cornelis sang it, but that it was when performed by Jailbird Singers. If we adopt Jersild and Jonsson’s argumentation, we avoid the need to split such hairs. Here prison songs are instead regarded as a system of song categories with various senders and receivers. At the centre of the system is a solid core, and its genre is indubitable — we can easily agree that these are prison songs.

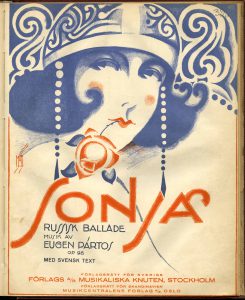

“Sonja”, with Swedish lyrics by Sven-Olof Sandberg. “Sonja” was released by the Odeon record company in 1928 with Sandberg as vocalist. To the right, a broadside from 1878 from Svenskt visarkiv’s collection: “The tale of the dreadful and gruesome murderer Nils Åkesson, who murdered his father, mother and brother on the 9th of April, 1877, and another song in addition”.

This work adheres to all intents and purposes to Bengt R. Johnson’s reasoning regarding emigrant songs (see above quote) and concludes that the core of the concept “prison songs” is songs about prisons, life in prisons, crime and criminal environments. The songs have in most cases been composed by prisoners, but to insist on this as an absolute condition for including a song in this genre would be to complicate demarcation to an unnecessary extent. On the diffuse periphery of this concept we find songs that are sometimes regarded as prison songs, sometimes not. Here we find, for example, songs from the popular music repertoire that romanticise prison life — songs like “Tjuvarnas konung” [King of the Thieves] or Sven Olof Sandberg’s hit song “Sonja”, the latter being a sentimental portrayal of the last night in the cell for a prisoner sentenced to death. Here are also to be found erotic songs sung in prisons, but also sung in other contexts — an important part of the material recorded. Another category on the periphery consists of songs that have been sung in prisons and which romanticise narcotics and their use. A category of songs close to prison songs are the so-called “evil-doer songs” or “malefactor songs” (Swedish: “missdådarvisor/malificantvisor) — spread as broadside ballads, particularly during the nineteenth century.

Many of these songs are about crime, and the action often takes place in prisons. Malefactor songs often first tell of a crime, then of what happens later: capture, sentencing and finally the punishment — often death. It is usually the malefactor who gives a first-person account. The words were, though, often written directly for the broadside medium by writers who had never had anything to do with prisons or prisoners. Whether or not these songs have ever been sung in prisons is not clear — what is clear, however, is that they are totally absent from the recordings at the Svenskt visarkiv. The matter turned out, however, to be not entirely without complications. There are, for example, hit songs and jazz standards in the material which have been recorded in prisons but have not been included in this study. The musical aspect of prison songs is also of interest. There are many prison songs with melodies of their own, but most — like broadside ballads, occasional songs and drinking songs — recycle well-known melodies. The use of familiar melodies was surely also of great importance for the survival chances of the songs. If the songs are to be spread, they must be able to be orally transferred from one person to another — and this is impeded if the tune is hard to remember.

The tunes too, first and foremost, the older category of songs stick to convention, using tunes familiar to a large part of the general public. Well-known tunes like “Alpens ros” [Rose of the Alp], “Lejonbruden” [The Lion’s Bride], “Apladalsvisan” [The Apladal Song], “Nicolina”, “Lili Marlene” and “När som sädesfälten böja sig för vinden” [On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away] are used for a number of songs. Melodically, these tunes bear the stamp of the musical conventions of the early 20th century: many are waltzes with distinct major melodics, often based on triads. It is also worthy of mention that the style of singing is in most cases typical of a popular song rather than a traditional folk song. Studies of traditional styles of singing show that a traditional song’s ideal differs in many ways from both art music and the ways of singing popular songs. The researchers Margareta Jersild and Ingrid Åkesson characterise the traditional manner of singing in the following way:

“The clearest common traits are a pitch close to the speaking voice, tonal placement far forward, a crisp approach to tones, individual variations of pulse and tempo, turns at the beginnings and ends of trills and melismas, distinct consonants and other speech sounds and a delivery in which every phrase is a unit.”

Using that perspective, we can observe that prison songs belong stylistically more to the domains of a popular song rather than to a traditional song. Singers of prison songs more or less generally use a greater range, often in a relatively high pitch, and clearly strive for a “handsome” sound — their goal is a sonorous, cultivated way of singing. They often glide into tones and use vibrato, which seldom occurs in traditional singing. Karin Strand writes that in the earlier broadside repertoire there were often couplings between the melody and original text and the new text, but that this connection ebbed away during the 1800s. In prison songs there is, however, often a connection between the text and the atmosphere created by the melodic language. The use of melodies in a minor key is however not as common as might be anticipated, because the songs often tell of sorrowful destinies. The melodies are by contrast often of the popular-music variety, often in a major mould in keeping with the conventions of the early 1900s. Strand also points out that “the associations of the original text can lie beneath as a meaningful pattern”. Some prison songs also refer to parts of the original text, not least by making parodies, as when Povel Ramel’s “Naturbarn” [Nature Children] contributed its melody to “Problembarn” [Problem Children], with the refrain:

Problem children, not be good.

Everything but problem children not worth having.

(“Problembarn” [Problem Children], Hall prison,1972)

“Hejsan gojting” borrowed both melody and text structure from Cornelis Vreeswijk’s “Brev från kolonien” [A Letter from Camp].

Hi, good looker, my only one.

Here’s a letter from your well-known

Post robber known as Jompis.

I’m sitting here and waiting for a crony.

(“Hejsan gojting [Hi, Good Looker], Hall prison, 1972)

The ethnomusicologist Märta Ramsten has described how the re-use of melodies in broadside ballads can be meaningful. This means that text and music interplay and their contents reinforce one another.

Kommentarer