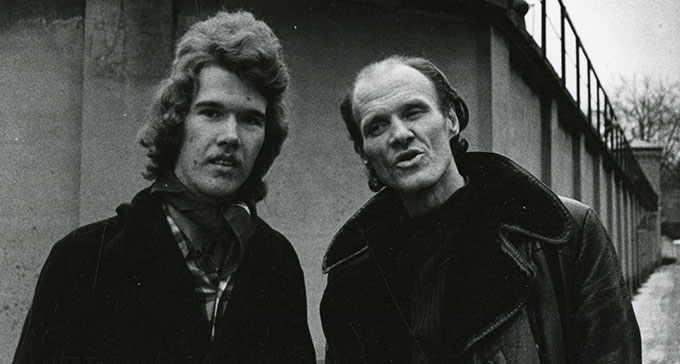

Robert Robertsson and Konvaljen outside Långholmen in 1973. The picture was taken for use on a poster and in press material. Photo: Allan Larson.

Lennart ”Konvaljen” Johansson

A number of key persons and organisations influenced the dissemination of songs and evolution of the genre “prison songs” during the 1960s and 1970s. The interest shown by record companies, with Metronome’s release of Jailbird Singers’ LP in 1964 — and later two LP’s from MNW — was of course of importance. Those tradition bearers who were interviewed point out a number of people as being particularly important. In some interviews, the interviewees refer to special paragons — other singers with good reputations and large repertoires. Bertil Sundin and Gunnar Ternhag devoted part of the interviews in their recording projects to asking about other potential informants. They ask who the informant learned the songs from and which other suitable persons the Svenskt visarkiv ought to visit and record. Several names are mentioned time and again: members of the Wigart family, Tony Granqvist from Jailbird Singers, a well-known jailbird and musician known as “Knutte-gitarr” and last but not least Lennart “Konvaljen” Johansson (1936 – 2021).

Konvaljen made a strong medial breakthrough with the LP Kåklåtar and became a name beyond the internal prison environment. Newspaper articles, TV and radio programs, and a large number of concerts turned him into something of a forerunner in the genre. This is mirrored in the collected material. He was given his nickname “Konvaljen” in a newspaper, Vänersborgs tidning, in connection with an escape from the county jail.

My name is Stig Björn Lennart Connvaij. With i-j at the end. Then there was a misprint when we escaped, like Lennart “Konvaljen” Johansson. Well, then… That was early. It was in 53, the first time we escaped from the Vänersborg clink. The next time we escaped it said “Konvaljen free and foot-loose again”, in that there Vänersborg paper. (Intervju 1996, Rolf Alm)

In an article published in Hallbladet (the prison newspaper), Konvaljen tells of the background to the recording of the LP Kåklåtar. Before he came to Hall he was imprisoned in Kalmar, and there he learned from a visiting theatre group that Gunilla Thorgren was trying to find clink tunes to make a record.

A theatre group came there one night and performed a play called Sherlock Holmes, a play about criminal care. One of the group’s members told me when we had a chat afterwards that a girl called Gunilla who worked at MNW in Vaxholm was looking for someone who could sing clink tunes. Since I knew loads of tunes and had also written some myself, I wrote a letter to Gunilla. Then time passed, I went off the tracks and ended up in the psychiatric clinic at Hall. One day I got a letter from Gunilla. She wrote that she was interested in meeting me to talk about an idea she had about making a record with clink tunes. One Sunday after that letter came, she came to visit. (Hallbladet nr 1–2, 1976)

Kåklåtar was recorded in MNW’s studio in Vaxholm in 1972. The recording has a clear stamp of the documentary. The arrangements are simple, and the impression given is that the entire production was the inspired fruits of the moment. This is consciously reinforced in the end product. Several tracks begin with small talk among the musicians, and they are heard to finger their instruments a little. A particularly clear example of this spontaneous atmosphere is “Konstapel Jöns” [Constable Jöns] in which the singer Jojje Olsson starts to sing “I natt jag drömde” [Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream] and the ensemble spontaneously join in one after another. Olsson plays around with the words, singing for example “there are no more inmates” instead of “there are no more soldiers” and the ensemble all laugh. After that, Konvaljen breaks in and takes command: “Constable Jöns! Let’s go!”.

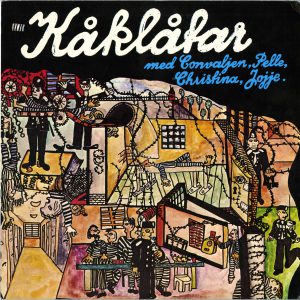

The front sleeve of the LP Kåklåtar from 1972. A work by the artist Bosse Kärne entitled “Jag har fastnat i straffmaskinen” [I got stuck in the punishment machine].

The main artists on the album were four inmates: Christina Calldén, Pelle Lindberg, Jojje Olsson and Lennart “Konvaljen” Johansson. Konvaljen is also named, together with Gunilla Thorgren and Anders Larsson, as producer of the record — and has a central role as soloist on six of the LP’s 15 tunes. In the collective of musicians there are also 14 more members.

In the autumn of 1974, Konvaljen moved to Växjö and his partnership with Robert Robertsson came to an end. Konvaljen was asked by MNW to record a solo album, and now he chose to work with other musicians. The LP Konvaljen was recorded in November 1974 and released in the spring of 1975. This is more of a studio production than Kåklåtar was. Instrumental parts are given much more room, and many of the tunes tend towards multicompositions and music theatre in which poetry and prose are read with instrumental backgrounds. Konvaljen explains that the recording was rather poorly prepared:

I didn’t have any texts. I was forced to talk. With a hell of a lot of musicians. So we took some accompaniment, and I just talked. And texts just came, like. I thought it was such bloody good fun, because it was good music.

The musicians came from MNW’s network of contacts. On the first track, “Resocialiseringsblues” [Resocialisation blues], Konvaljen is accompanied by the progressive rock group Samla Mammas Manna. A prominent role is played by the blues pianist Per “Slim” Notini and the album as a whole has a “bluesy” character. Konvaljen states in an interview that many of the compositions came into being in the studio and that he himself was not as well-prepared as he had been when Kåklåtar was recorded. The recording process was more time-consuming, too, since half-baked ideas were tested directly in the studio.

Konvaljen had a short but intensive career as a professional artist and debater. When interviewed, he himself says that the period from 1972 to 1977 was unique and that it changed his life in many ways. Two records, lots of appearances on the radio and TV, and all the attention shown by the press had made Konvaljen a well-known person who was associated with the progressive music movement.

Kommentarer