Erik Gustaf Geijer: The Hopeful Romantic

Margareta Jonth, Carl Rune Larsson, Nils-Erik Sparf, James Horton, Lars Frykholm, Lucia Negro, John Forsell, Wilhelm Stenhammar, Akademiska kören, Tor Mann, Allmänna sången, Henry Weman, Orphei Drängar, Eric Ericson

The musical legacy of writer, poet, philosopher, historian and – most relevant for this context – composer Erik Gustaf Geijer (1783–1847) is represented here with an exclusively digital compilation of all of Caprice Music’s recordings of his masterful, but tragically almost forgotten music. Here is a wide musical selection of both his more frequently performed melodies such as “Kväll och frid” and “Svanvits sång”, and more unknown works such as his dramatic Piano Quartet in E minor and heartfelt songs for voice and piano.

This extensive compilation album is available to stream and download on most digital outlets, such as Spotify, Tidal, and Apple Music.

E.G. Geijer, oil painting by J.G. Sandberg, 1828.

Erik Gustaf Geijer (1783-1847)

In German cultural circles the expression the Goethe era is an accepted term; few would question the justification of using those words to describe the period 1749-1832, which was the master’s lifetime – or at least 1770-1832, which was his active time. We take it for granted that the “Olympian of Weimar” dominated an age which nevertheless was by no means lacking in geniuses.

If one particular Swede apart from the sovereigns – with similar arguments could claim to be elevated to the key figure of an epoch, the choice would probably fall on Erik Gustaf Geijer. In several spheres which, at any rate, those in prominent positions regarded as essential, he embodied Sweden’s approach to romanticism, the religious self-control and conservative self-examination of the early 19th century. He also embodied the transition to “modernity” – to liberalism and individualism.

On this journey, which was often arduous, he took with him from the peaceful country-house life in Värmland, where he spent his childhood and youth, provisions which were indispensable and which gave his long intellectual, religious, and moral life decisive traits of great humanity: love of the forests and mountains, songs and music, the lyrical gift. Without these provisions, which he generously shared with others, the thinker and historian Geijer would probably have had to walk alone on the usual professor’s path.

Now he became, as far as an individual can be, an inspirational leader. After his death, his memory, at least in the small academic town of Uppsala, proved a heavy weight to bear. The Geijer cult – discreetly upheld by his daughter Agnes, Countess Hamilton and mistress of Uppsala Castle, by her husband the governor, and by a generation or more of historians and philosophers up to the storms of the 1880’s – became part of the dreamy Late Romantic echo’s self-defence against everything new. The cult became a burden. But that was not Geijer’s fault.

Geijer was born at the manor house of the iron foundry at Ransäter in the province of Värmland, on

12 January 1783. His father’s side came from a German bourgeoise family who had gone in for mining; his father, a capable mining engineer, was ironmaster at Ransäter. On his mother’s side too – where intellectual talents and inclinations were more prominent – Geijer came of a middle-class family of German origins.

In Geijer’s Minnen (“Memories”, 1834), life at Ransäter is described with a loving freshness, witnessing both to the ability of one’s childhood surroundings to live on in the rose-tinted light of memory, and to the ageing Geijer’s unbroken creative power and emotional intensity. At a distance of almost 250 years, the home at Ransäter, with the stern father and the silent, subdued mother, may seem narrow and harsh. It was a manor house in which the 20-year-old had to purloin the candle-stumps he needed in his room at night to write, in secret, the work that was to bring him youthful fame – the memorial to Sten Sture the Elder (1803), which was awarded the Grand Prize of the Swedish Academy. The house still has a palpable atmosphere of Sweden in the rustic 18th century days of poverty, with a lingering Carolinian austerity.

But there was dancing and music-making; there were books, and nature had been discovered as a source of strength and joy. In Geijer’s “Memories”, Ransäter is a paradise, without overbearing sentimentality:

The sap of the spring greenery, the coolness of the forest shade, the invigorating freshness of the billows – the scent of spruce and flowers – country air, morning air – all this lives and is present in this memory; and town life, indoor life, books galore, all the dust on the path of learning have not been able to wipe it out.

One of the fundamental experiences outside the path of learning strewn with book dust which became Geijer’s career, was a journey (1810) to the England of the Napoleonic wars and early industrialism. There he had the opportunity of studying the world at large, and the strength and weaknesses of a free, wealthy, and open society. Otherwise, Geijer was not much of a traveller.

From 1799, when the 16-year-old set out for Uppsala, until 1846, when as professor emeritus he left it to spend the last year of his life in Stockholm, he remained in the university town with only a few short breaks. To an even greater extent than now, an academic career in those days meant long, financially lean times of waiting – accompanied by lengthy engagements and much letter-writing – and Geijer’s career was no exception: unpaid lecturer in 1811, acting professor of history in 1815 (the first paid post) and finally, in 1817, permanent professorship. In the summer of 1816, after a betrothal of seven years, he married Anna Lisa Lilljebjörn, a girl from the neighbouring estate in Värmland.

Geijer reflects his century. He follows many tracks. From 1803, we have the memorial to Sten Sture, an 18th century eulogy in the French academic style, but also learned dissertations in the University Latin of the age. From 1810 until the middle of the 1820s, Geijer wrote Gothic* poetry – Odalbonden (“The Yeoman”), Manhem, Vikingen (“The Viking”) – hymns, but also aesthetic and political theses in the spirit of new romanticism and conservatism. Geijer became the theorist of the Swedish, and above all the Uppsala reaction, but he was not “reactionary” in the real sense.

The journey to England, the Värmlandian liberalism with echoes from the Swedish Age of Liberty’s tradition (1718-72), and his own independent reflections on history and society, saved him from narrowminded attitudes. In religious matters he remained so openly liberal that he incurred a press lawsuit; his subsequent acquittal strengthened his faith in a free social order.

From the 1820s, the research and writing of history predominated. At the same time, Geijer’s famous “defection” was being prepared: his change from fundamental conservatism to a moderate liberalism. Besides historical works and extensive writings with a philosophic, social, and political outlook, the last ten years of his life produced a small collection of very personal lyrical poems. Geijer’s “Memories” belongs to this final phase of his development. And all his life, he performed and composed music. In a concise but masterly way, he has characterised his relationship to music in the poem Tonerna (“The Tones”):

“Thought, whose struggles only the night sees,

Tones, with you it begs for rest!

Heart, which suffers from the day’s tumult,

Tones, to you, to you it wants to flee.”

The final point in Geijer’s intellectual development was what he himself called the philosophy of personality: a conception of the world and of life in which, on the basis of what he had learnt in his full life, of his observations and reflections, he succeeded in combining warm personal piety, respect for the individual – even the most insignificant person’s ego as a building stone in the universe, as well as faith in human and social fellowship as an essential condition of life. In this philosophy, which had great influence on generations of Swedish teachers, clergymen and civil servants, the strongest element is faith in a personal contact with God. The poem Natthimmelen (“The Night Sky”) may serve to sum up the mature, ageing Geijer’s outlook on life:

“Alone I advance along my course,

farther and farther extends the way;

alas, my goal is hidden in the distance.

Dusk is falling. The sky turns to night.

Soon the eternal stars are all that I see.

But I do not lament the fleeing day,

the coming night does not appal me;

for of the love that goes through the world

a ray also shone into my soul.”

Stig Strömholm, 1982

Vice principal, Uppsala University

*A cultural movement inspired by Nordic pre-historic times, especially located to Uppsala.

About Geijer, the composer

The versatile Erik Gustaf Geijer was active in many spheres, and in an often quoted remark from 1836 he says he has practised as many pursuits as the fingers on one hand, counting from the thumb philosophy, history, eloquence, poetry, and music, all of which he has exercised in honest craft and is unwilling to give up any, not even the pinky. He could have added politics, social issues, and the whole of his pedagogic work, but then one hand would not have been enough!

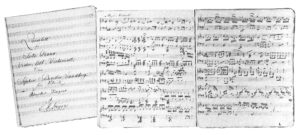

In his “Memories”, Geijer says that he was brought up with dance and music, diligently played the piano and while still an adolescent at Ransäter had been driven to try my hand at composition, without knowing its rules. The first time a composition by Geijer is expressly mentioned is in one of his letters in 1801, which is about a piano sonata he had written at Uppsala University, which had caused something of a commotion among his musical friends at home. The earliest extant composition appears to be the song Minne (“Memory”) (Whom do I seek? Whom?), the tune of which is given as being from 1805, though the text is from much later. When, during a journey to England in 1810, Geijer writes two large piano works – a Sonata in G minor and a Fantasia in F minor – he shows an assured mastery, both of the thematic development technique and the formal plan of the work as a whole. He had previously taken lessons in theory and composition from Pehr Frigel (1750–1842), and it appears from letters that, at times, he had planned to devote himself entirely to music.

Then, in the early years of the 1810s, came Geijer’s remarkably quick breakthrough as a poet in the Gothic spirit, and he wrote music to several of these poems – Vikingen (“The Viking”), Odalbonden (“The Yeoman”) and Den lille kolargossen (“The Little Charcoal–Burner Boy”), among others. The tunes have the simplicity of a folksong, reminding us that Geijer, with his collection Svenska Folkvisor från forntiden (“Swedish Folk Songs of Yore”) – published 1814-1817 together with Arvid August Afzelius (1785–1871) – is one of the pioneers of Swedish folk music.

Towards the end of the decade, when he was made a permanent professor of history at Uppsala, Geijer, at regular intervals during the next ten years, wrote a number of impressive chamber music works: a violin sonata and two “double sonatas” for piano duet 1819 – 20, a string quartet 1822, a piano quintet 1823, a piano quartet (recorded here) 1825 and a piano trio 1827; one of the violin sonatas, a cello sonata and several string quartet movements probably date from the same time.

In 1824, together with Adolf Fredrik Lindblad, Geijer published a booklet Musik för sång och pianoforte (“Music for voice and pianoforte”), which contained a “divertimento” for piano in addition to five songs and a quartet for male voices. A second “divertimento” followed in the collection Nordmannaharpan (“The Northman’s Harp”) in 1832. Between 1834 and 1842 a song booklet by Geijer appeared almost annually, in which older and more recent compositions were mixed. A ninth and last booklet was published in 1846. During these later years, which were full not only of everyday worries, but also of all the problems that his political front change entailed, Geijer could only sporadically compose in instrumental form, and a few short piano pieces, a string quartet movement, and a movement for violin and piano were all that was written down.

Geijer’s songs have come to be regarded as some of the “minor classics” of Swedish music and have been sung quite frequently up to the present day, while the instrumental works have been almost totally neglected, possibly with the exception of the piano compositions that Geijer himself published, and of the piano quartet that was printed in the middle of the 1860s.

While Geijer in his songs, in a natural and sensitive way, conjures up moods and situations that are both personal and general, in his chamber music he is chiefly the classicist, who, having learnt from the great Viennese masters and having a keen ear for the burgeoning romanticism (Weber, Mendelssohn), fashions well-constructed sonata, variation, and rondo movements. Geijer’s compositions certainly have two sides, which of course at times can be combined; behind the songs is the skilful improviser at the piano who joined his musical ideas to the verse patterns of the words, and behind the chamber music is the Geijer who practised composition as a deliberate intellectual training and as sharpening of all his senses. He has himself stated how the piano quartet simply developed in his head during his travels in Germany in 1825 together with Lindblad and Malla Silfverstolpe.

If there is a perceived unevenness in his chamber music, one should bear in mind that it was not intended for public performance, but for intimate social gatherings, in which the demands could admittedly be high, but in which the composer himself could step in and exchange or revise movements. As a result, the chronology of Geijer’s musical production has become a trifle confusing, and a “new” composition does not always mean a “newly written one”. Regarding the Piano Quartet, it need only be added that the two brisk outer movements are in fairly strict sonata form, that the slow movements is an andante cantabile in Lied form and that the third movement is one of Geijer’s many stylized minuets, here with two contrasting trios. The version recorded here is the printed posthumous one from 1865, considerably edited compared to the autograph.

Geijer’s songs can suitably be divided into four categories: nature scenes and mood pieces of a more general kind, genre pictures in the style of the age, humorous or sententious reflections in a kind of epigram form, and deeply personal meditations with a serious and often religious undertone; the composer reserves more patriotic feelings for his choral pieces.

The present selection gives examples of all kinds of songs, and on the side, it also contains a little solo scene with words from Bengt Lidner’s opera libretto Medea, which shows yet another side of Geijer’s musical receptivity and at the same time his natural sense of dramatic declamation. Most of the songs, despite their limited format, were also intended to be performed very freely and graphically, with clear enunciation of the text.

Oddly enough it was the composer’s friend and colleague Lindblad who, in the preface to the first edition of Geijer’s collected writings in 1848, gave rise to the general opinion of Geijer as a composing dilettante – a view of the brilliant Uppsala professor’s music that has been predominant for far too long. Lindblad no doubt felt justified in his judgment, since he had several times “corrected” technical faults in Geijer’s piano parts before the publication of the song booklets. But he seems not to have perceived the durability of his friend’s chamber music, nor to have sensed that even his own instrumental music would be rejected by the Swedish 19th century’s public opinion with its condescending attitude to the problems of works on a large scale – the attitude that literally exiled Franz Berwald.

It has taken a long time to reassess Geijer’s and Lindblad’s works and much remains to be done, but now the time should be ripe for a wider and more generous view of their music. Granted that Geijer was not a professional composer, but his compositions have such valuable external and internal qualities that they are well worth their renaissance with both performers and listeners – Swedish musical history would be much the poorer without them!

Lennart Hedwall, 1982

Composer, musicologist, and conductor

Producer and editor: Erik Hamrefors

Translation: Alan Blair

Omslagsbild: Midjourney AI

-

1.Aftonbetraktelse (instrumental version) Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

2.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 1: No. 3, Blomplockerskan Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

3.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 1: No. 4, Bilden Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

4.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 3: No. 3, Gräl och allt väl Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

5.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 3: No. 6, Första aftonen i det nya hemmet Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

6.Songs for Men's Chorus: No. 27, O yngling, om du hjerta har Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

7.Songs for Men's Chorus: No. 28, Svanvhits sång Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

8.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 4: No. 5, Ur Lidners Medea Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

9.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 5: No. 7, Sångerskan Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

10.Piano Quartet in E Minor: I. Allegro moderato Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

11.Piano Quartet in E Minor: II. Andante cantabile Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

12.Piano Quartet in E Minor: III. Menuetto Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

13.Piano Quartet in E Minor: IV: Allegro Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

14.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 2: No. 7, Skärsliparegossen Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

15.Songs for Men's Chorus: No. 29, Aftonbetraktelse (Qväll och frid) Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

16.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 9: No. 4, Den nalkande stormen Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

17.Songs for Men's Chorus: No. 28, Svanvhits sång Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

18.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 6: No. 6, På vattnet Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

19.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 6: No. 1, Aftonklockan Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

20.Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Book 8: No. 8, Han Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

21.Songs for Men's Chorus: No. 33, Karl XII:s marsch vid Narva Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

22.Songs for Men's Chorus: No. 29, Aftonbetraktelse (Qväll och frid) Music: Erik Gustaf Geijer

-

- Total playtime