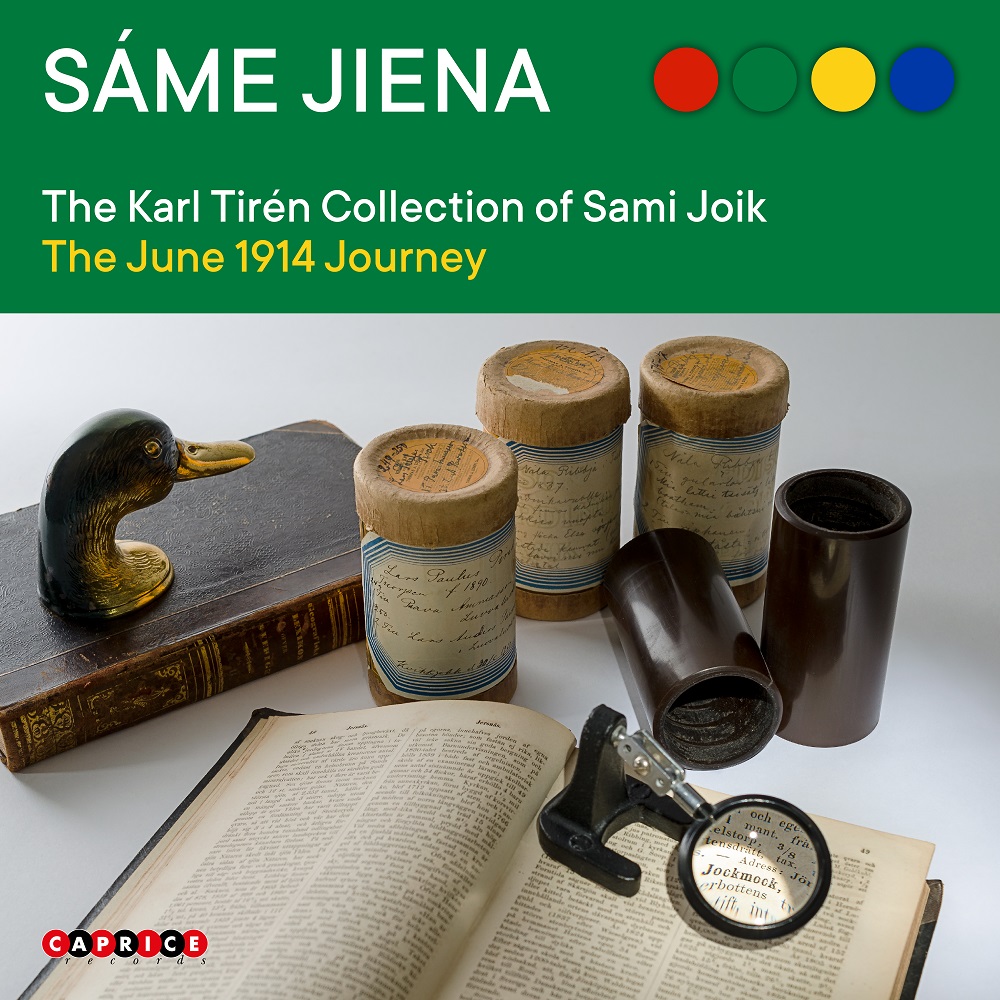

SÁME JIENA – The Karl Tirén Collection of Sami Joik: The June 1914 Journey

Nila Ribbja, Lanni Nilsson Saulo, Nils Juvva Pirak, Lars Paulus Pirak, Nils Persson Pavval, Johan Anders Holmbom, Lars Holmbom, Anders Paulus Andersson Hulju, Daniel Nilsson

This is the fourth of six volumes with field recordings of Sámi joik singing made in the 1910’s.

In the fall of 1912, musicologist, stationmaster, artist and violin maker Karl Tirén (1869-1955) was offered the loan of a phonograph and pertaining wax cylinders from the Swedish Museum of Natural History’s ethnographic department, with the instruction of recording Sami traditional singing (joik), storytelling and other verbal traditions. The apparatus itself was among the marvels of the modern age, and had been purchased in Berlin just a few years prior. Acquiring Sami objects for the museum’s collection was also part of the ethnographic department’s mission.

This fourth volume contains recordings from the travels Tirén undertook in June 1914, to Tuorpon village och Jokkmokk.

Sami joik

The joik is a particular way of singing, which was developed by the Sami. Besides the voice technique, the main difference between joik and other types of song in the Nordic region is the relation between the song as an aesthetic expression and its content.

Joiking a person or animal

Traditional joiks relate to what has been described as a reference object; this may be a person, an animal or a place. A performer does not joik about a particular person or animal, but rather joiks that person or animal, which is to say, giving them a musical formation in performance, influenced by the joiker’s perception and appreciation of their qualities.

These joik melodies are used by social groups, so that the joiks become a form of musical name for the reference object, which many Sami can recognise and perform at different times. For example, during Karl Tirén’s recording sessions it sometimes occurred that when a new person came into the room, one of the present joikers would begin to perform the ‘personal joik’ of that individual, as a means of welcome and of confirming his or her relationship with them.

Musical characteristics

It is often possible to identify joik through its approach to the voice and timbre – often sung with what has been described as a “pressed” or “pinched” voice, and a rich use of ornaments and glissandi between notes. When joik melodies are represented in musical notation, it is not unusual to see asymmetrical time signatures (for example, 5/8, 7/8 or 11/8), with the melodies often being cyclical, so that the performance may continue for as long as the joiker desires, or the situation allows.

The Swedish verb jojka is derived from the Sami juiogat. In Swedish, the act of joiking has increasingly come to be known as joik. Quite simply, you joik a joik. The Sámi terminology is rather different. In the Northern Sami language, one joiks a luohti (plural luoðit), in Lulesami, a vuolle (plural vuole) and in Southern Sami, a vuelie (plural vuelieh). For the performance of songs and hymns the terms lávla, singing, and lávlut, to sing, are used.

The first joik encounter

Karl Tirén’s first impression of the joik came via meeting Lars Erik Granström at the big Luleå fiddler competition in 1909. After that, Tirén was hooked – collecting, exploring and publicising the Sami musical culture would accompany him for the rest of his life. Later that same year, Tirén met wood turner Maria Persson. She became his most important informant and guide in the Sami joik tradition, something very few had been privy to before.

The first recording trips, to the winter markets in Arvidsjaur and Arjeplog, were made in February 1913. In July that year, Tirén made a collecting journey which he started off by making more phonograph recordings, mostly in Tärnaby in conjunction with a so called Prayer Day. He also chronicled several joiks onto paper by ear.

In January 1914, Tirén visited the winter markets in Lycksele and Åsele, continuing his recording work. The summer of 1914 resulted in recordings from a trip to Jokkmokk and Kvikkjokk in late June, as well as in July in connection to the governor Walter Murray’s meetings with reindeer keeper at various locations. Tirén’s last field recordings with the phonograph were made in October 1915, when he was invited as a guest to Maria Persson’s (afterwards, Persson-Johansson) wedding.

Phonograph – the first recording technology

he phonograph was the first technology for recording, storing and reproducing sound. The device was invented by Thomas Edison in 1877, but only came into wider usage from the 1890s, due to the change from tinfoil to wax cylinder as the audio carrier.

The phonograph is a purely mechanical technology that does not require electricity to operate. Compared to modern recording equipment, a phonograph has neither a microphone, amplifier or speakers. The wax cylinder is usually rotated in place by means of a clockwork spring.

Karl Tirén and the phonograph

Karl Tirén had learned to use a phonograph from Yngve Laurell at the Ethnographic Museum, whom in turn had acquired the technology at the then world-leading research archive on folk music from around the world, the Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv in Berlin.

On Tirén’s recordings you can hear him pre-announcing the next item, according to the Berlin archive model – who will joik, and what will be joiked – indicating the reference tone by blowing a pitch pipe with the then-current standard tuning pitch (A=435 hertz).

From Arvidsjaur to Africa

This mechanical technology, and the fact that it was possible to make the devices fairly small and portable, made the phonograph a popular technology for documenting speech and music during collecting trips and expeditions to remote areas.

Alongside Karl Tirén’s joik recordings, at the winter markets in Arvidsjaur and Arjeplog in 1913, the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm in the 1910s supported several other expeditions to Africa, Australia, South America and Greenland. In addition, the archives of dialects and folklore in Sweden also made ethnographic phonograph recordings during this period.

Recording and playback

Recordings were made by singing or playing into the phonograph’s horn. At the narrow end of the horn is a sound box containing a diaphragm, to which an engraving needle is attached. The diaphragm converts sound waves into movement; following these movements the needle engraves a groove in the rotating wax cylinder.

For listening, the process is reversed by switching to a sound box with a blunt needle. The needle follows the contour of the audio track in the rotating wax cylinder, and the diaphragm converts the movements into sound waves, which are then amplified through the horn.

Difficulty in labelling wax cylinders

Unlike gramophone discs, which had a label in the middle, it was difficult to label wax cylinders. Instead, recordings would be introduced or concluded with a spoken announcement, describing what was on the recording – usually a pre- or post announcement.

Phonographs also had variable speed control – the faster the recording speed, the better the sound quality, but at the cost of a shorter playing time. The correct playback speed was therefore sometimes determined by the sounding of a reference tone.

Transfers of Tirén’s recordings

When phonograph cylinders are transferred today, this is accomplished by the use of more modern, electrical equipment. Karl Tirén’s phonograph recordings have been transferred a few times in recent decades. In 1984, they were transferred onto audiotape by Anders Schilling at the then national audio-visual archive (today the audio-visual collections of the National Library of Sweden). Around 1990, another transfer was made at Swedish Radio by Mats Brolin and Inger Stenman.

About the recording:

Producer och technician: Karl Tirén

Technical assistance: Karl-Erik Forsslund & Maria Persson

Digital restoration: Torbjörn Ivarsson

Cover photo: Narciso Contreras

Graphic design: Jonas André

Translation to Sami: Miliana Baer

Translation to English: Robin McGinley & Erik Hamrefors

-

1.Den förtvivlade brudens sång - Ollo Länta i Aktsetrakten Music: Traditional

-

2.Familjefaderns hemliga läten för att underlätta familjen då han ämnar offra - Då han varnar innan raiden passerar en offerplats Music: Traditional

-

3.Till Stora Lule elv - Till Pellorippe Music: Traditional

-

4.Kadnikavuolle - En ung flicka Elsa sörjer sin mistade kamrat Music: Traditional

-

5.Hemlig sång till familjen, då lappen går att offra Music: Traditional

-

6.Till gulärlor - Till riphanen - Till svanen Music: Traditional

-

7.Till ekorren - Till smålom - Till storlom Music: Traditional

-

8.Till Pera (nomadlapp i Jokkmokks lappby, död 1800-talet) - Till räven (vanliga) Music: Traditional

-

9.Karin Pankas Juckel sorgesång - Pitar Saras Vallarlåt Music: Traditional

-

10.Vallarsång - Till fadern Nils Påhlsson Saulo Music: Traditional

-

11.Till Snierak - Till Tarrekaise - Till Pårtefjällen Music: Traditional

-

12.Till Tuorpenjaur - Till Anders Gustaf Sjulsson - Till Per Hombo Ruong Music: Traditional

-

13.Sin egen vuolle som fiskarlapp - Sin vuolle som nomadlapp Music: Traditional

-

14.Vallning på fjället Music: Traditional

-

15.Till Ålmajalosjägna (Sulitelma) - Till Kappatjokko (Stora sjöfallet) Music: Traditional

-

16.Till Lars Paava Ammasson i Luvvaluokta - Till Lars Anders Pavasson i Luvvaluokta Music: Traditional

-

17.Till Silbatjåkko (norr om Tarrätno) - Till Anna Magda (Pavval) Kuoljok i Tuorpen Music: Traditional

-

18.Vallarlåt - Jojklåt i fjällen Music: Traditional

-

19.Bred skalle är död (björnsång) Music: Traditional

-

20.Iggals sång till björnen Music: Traditional

-

21.Riplåtar Music: Traditional

-

22.Vallarlåt - Jojkning, då man är ledsen över att ha mistat renar Music: Traditional

-

23.Då han sitter på fjellet - Till gamle Nila Paval, fjällets rikaste gubbe (?) Music: Traditional

-

24.Riplock Music: Traditional

-

25.Tjäderlock Music: Traditional

-

- Total playtime